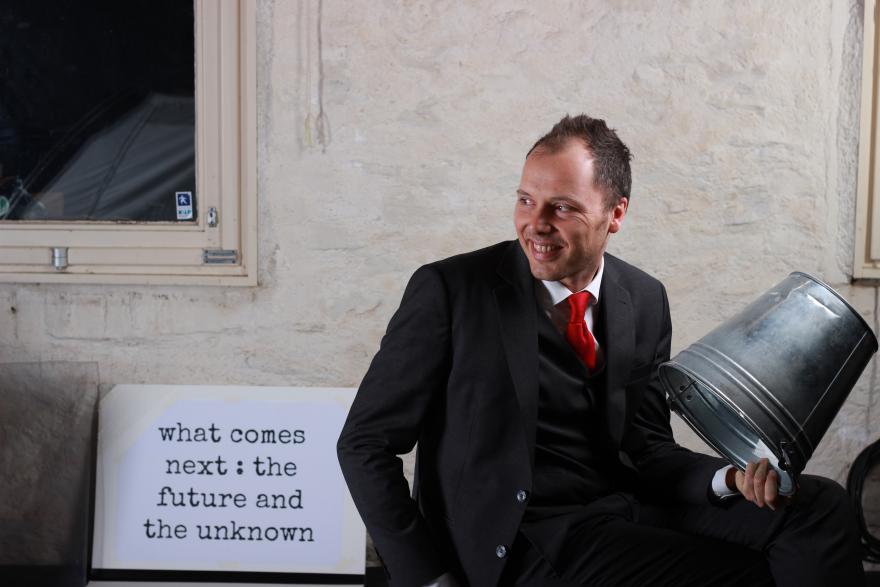

Guy Waerenburgh on circus, life and the way of things

With a chain reaction of tin buckets, towers of bricks and spinning plates, Der Lauf der Dinge (‘The Way of Things’) is an invitation for the audience to completely let go. Juggler Guy Waerenburgh combines unabashed entertainment and innocent (?) audience participation with unexpected philosophical wisdom. ‘Welcome. This is not a show.’

It’s an unusual sight for a train station: a man with a tin bucket on his head. Standing among seasoned commuters who can’t wait to steal some extra shut-eye on the train. A gaggle of giggling 15-year-olds take selfies. Others, who shake their heads and tut at what’s become of this world. The security personnel are ready to shut down any disturbance that may be brewing, but they allow him to continue, for art’s sake. The man’s sign reads 'Ceci n’est pas un spectacle’ – a clear reference to the painter Magritte, Belgian Surrealism and the spirit our artists have become known for. Guy Waerenburgh may have lived and worked in the north of France for years now, but his roots remain as unmistakable as his West-Flemish accent.

“I was born in Mouscron, but I went to school in Kortrijk. One day I found myself once again waiting for the train and, out of boredom, I picked up three stones and began to juggle. Together with Hans Vanwynsberghe and Matthias Vermael, I started a juggling club we called Gravité, and things started to take off from there. I never attended a youth circus or had any professional training. After high school I went to university to study philosophy, though to say I studied is an exaggeration. I mostly juggled, since the auditoriums there had ceilings that were the perfect height. I never even picked up my diploma. Why would I? It was completely useless to me.”

It was at that time that Guy started to juggle with friends in Lille during festivals, at private events and cabarets. He did especially well with Mambo Circus, a double act he performed together with his wife Anne-Agathe Prin (who is now the promotor for Collectif Malunés, Cie De Fracto and Les Fauves, ed.). “I played a macho juggler, with Anne-Agathe as my lovely assistant. It was pure parody, though we must have been a bit too convincing at times, as many organisers didn’t seem to get the joke”, laughs Guy.

Ten years later, Guy was invited by Cirque du Soleil to travel to Macau and perform in a juggling act with Gandini Juggling. “My wife was pregnant at the time and couldn’t perform, so that was an offer I gladly accepted. One year eventually became two.” He’s critical when he reflects on his experiences there. “Outsiders would think that if you’re performing with Cirque du Soleil then you’ve really made it. I will say that it was nice to finally have the respect of my parents. They were both doctors. When I was young, they would snatch my juggling clubs and hide them in their bedroom. They saw little future in a career with the circus. It was only when I started to work with Cirque du Soleil that they dared tell their friends that I was a juggler.

“Unfortunately, reality always turns out differently from your dreams. It’s a tempting life, though. At Cirque du Soleil the pay is very good, and you get spoiled by a whole legion of personnel who are there to look after your needs. But the flip side is that you become your own prisoner: Macau is one big gambling and sex-trade capital, with just a few big shows to see. In the end, you’re just a performer, so you can forget about artistic freedom.”

Celebration of failure

For Guy, after a career of some twenty years, Der Lauf der Dinge is a completely different experience: having only worked performed shorter acts in the commercial circuit, and being primarily a fan of traditional juggling, for the first time he has been able to create a longer performance that flirts with the codes of both classic cabaret acts and contemporary circus. “A while back I had a spinning plates act that I would do at private parties. I had refined my technique to the point that Eric Longequel (juggler with Cie Ea Eo and De Fracto) joked that I could probably do it with a bucket over my head. Eric saw the possibility of taking it in a very different direction.

“It’s a completely different way of working: for a short act you just need to have one good idea and perform it. Now, all of a sudden, I’m occupied with the shape of the entire piece, with intentions, with dramaturgy, even!” Guy laughs. “I’m experiencing for the first time the peace of mind and freedom that comes with creating for yourself. It’s a completely different world from the private circuit, where you’re performing as people are eating their dinner. It’s an incredible luxury to work on something that aspires to achieve more than the instant gratification of the audience.”

He has often wrestled with the obligation to live up to expectations of others, be they parents, a mega-circus or the organisers of a private function. For this project, breaking free of the need to ‘achieve’ something, artistically but also mentally, was essential. “Der Lauf der Dinge is the complete opposite of a juggling act in which everything has to go as planned, where everything has been determined beforehand: how many balls, how they are thrown, the rhythm of the music. It’s like a dream come true. Normally, if you drop a ball, then the act is a failure. At one point I really had difficulties with that, and the stress paralysed me. With the kind of perfection I was aiming for, I couldn’t help but disappoint myself. That’s why Der Lauf der Dinge is such a breath of fresh air. If I screw everything up, then that’s just part of the game. It isn’t embarrassing, you know? It allows me to be fallible. Instead of maintaining the dream at any cost, I can embrace the imperfections and accept that things just go the way they go.”

Breaking out of yourself

The performance Der Lauf der Dinge is based on a film of the same name from 1987. In the film by Peter Fischli and David Weiss we follow a series of chain reactions unfolding over the course of its 29 minutes and 45 seconds. Various objects – car tires, ladders, chairs, balloons, wooden beams and planks – can be seen burning, falling, melting and exploding. In Guy’s act, the audience also watches as things unfold in different settings. However, his chain reactions all harken back to carnivals and cabaret: the cup and ball trick, knocking over cans, spinning plates on a stick. And there’s always a little twist.

Who would have thought that this classic shtick could still evoke such a reaction from the audience? “Number 1! Number 2! Number 6!” they shout as Guy tries to control the plates on sticks with a bucket on his head. The kids scream until they’re hoarse and – when they finally overcome their sheepishness – so do the adults. “Adults often don’t realise how bound they are to the etiquette we impose on ourselves. During the show you can see them, at first a bit hesitant as they give their children permission to have a bit of fun with that old fool up on stage, but at some point you watch them forego all restraint and go wild. For me that feels like a victory”, Guy smiles. “When I did a try-out school performance at Le Prato in Lille, one class got so excited that the technicians went looking for assistance because they thought it surely wasn’t intended to go off the rails like this. But it’s not just chaos that I’m creating: you can also see how it incites the audience to join together to guess the right bucket, for example.”

Innocent fun?

A superficial reading might leave one with the impression that Der Lauf der Dinge is purely entertainment, but the participatory aspect reveals that other mechanisms are at play. It’s a major tipping point when the audience starts to join in. That moment when the silence is broken, first in quiet whispers, then in screams that increasingly swell as everybody indulges in the freedom to react with abandon. Some will shout out the right numbers during the spinning plates act, while the rascals in the audience will take great pleasure in shouting out the wrong numbers in an attempt to get the plates to fall. Because that’s human nature: empathy and perversion in equal parts. We admire those who are successful as much as we enjoy watching other people fail. Life in a nutshell. In this way, Der Lauf der Dinge is a society in microcosm, in which people work both with and against each other. Playing with expectation and surprise, a devilishly clever power game is developed between performer and audience.

Guy himself describes the piece as a cross between It’s a Knock-out and a David Lynch film. A good example of the show’s absurdity comes in the form of the dubious figure in a rabbit costume who throws the audience candy as a reward. It’s a blatant criticism of the entertainment industry that Guy knows so well, and, as audience members clamour for a piece of candy, one can’t help but think of the ‘bread and games’ of ancient Rome. What starts out as light and playful can just as easily turn into aggression. Especially when the individual mindset gives way to mob mentality. Der Lauf Der Dinge evolves from seemingly innocent fun into an allegory for politics. In the final act, again referring to the carnival game of knocking over cans, things degenerate into what Guy calls ‘the stoning’: a purifying ritual, a catharsis, in which the audience liberate themselves.

At the start of Der Lauf der Dinge the audience receives a text that seems to be about how the show will unfold. But if you read the text after the show, it turns out to be about life itself. Perhaps that course in philosophy was good for something after all. Guy is right: this is not just a show.

This article was originally published in Dutch in Circusmagazine #62 – March 2020 // Author: Liv Laveyne // Pictures: Michiel Devijver // English translation: Craig Weston, edited by Jonathan Beaton